Simon Devitt Photographed The Alexandra House in Central Otago for Home Magazine. Design by Anne-Marie Chin Architects

Simon Devitt Photographed The Alexandra House in Central Otago for Home Magazine. Design by Anne-Marie Chin Architects

Simon Devitt Photographer of Architecture for Home Magazine images of The Bunker House design by Dalman Architects

Towards an old architecture

From Architecture New Zealand – March 2024 (Issue 2) Words Anthony Hōete

New Zealand is a small country with few architects. Where Britain has 42,170 registered architects in a population of 67 million, or one per 1600 persons, New Zealand has rather fewer, with one architect per 2200 persons.1

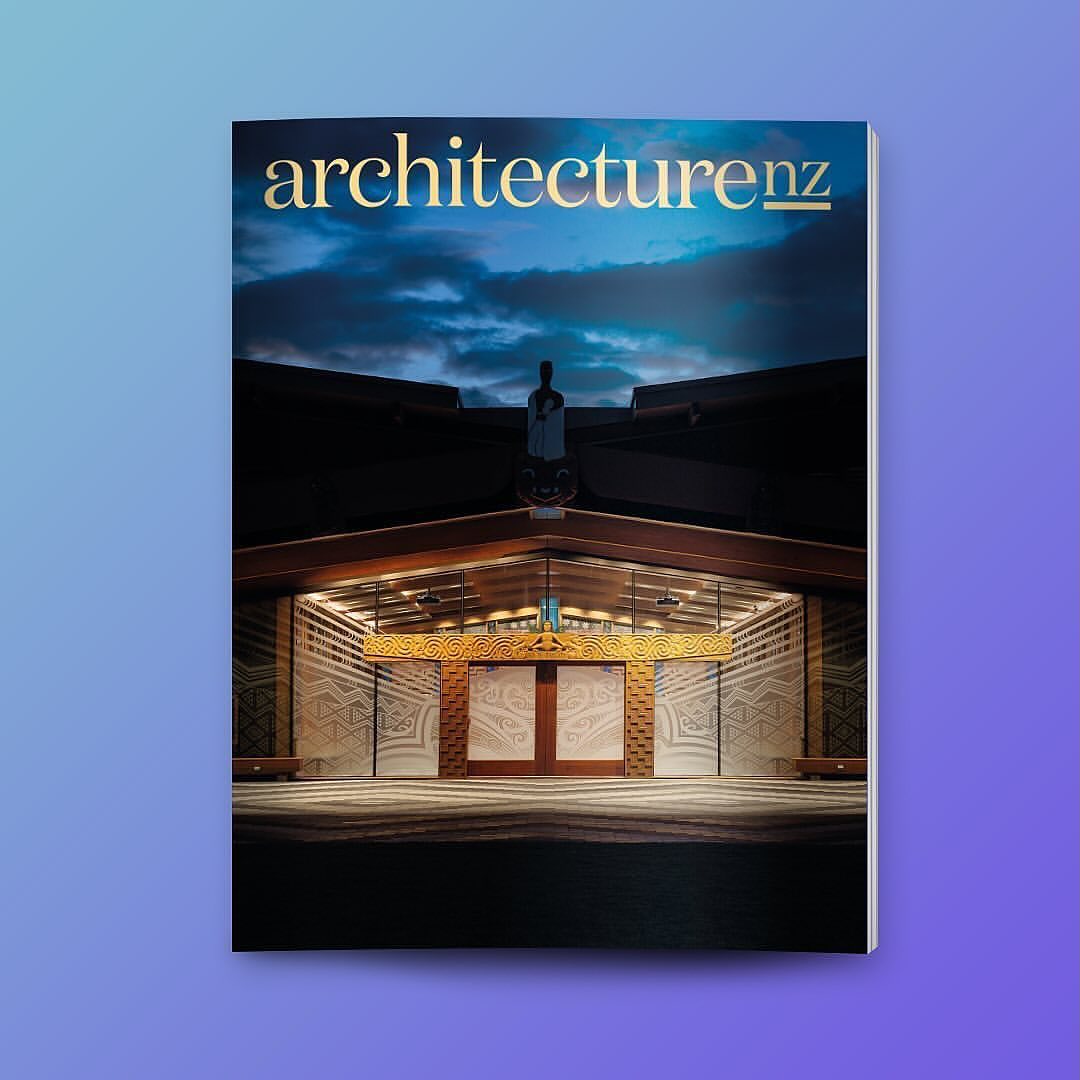

A Pā is strategically located, with the summit reserved for rangatira. As the last line of defence, a Pā assumes the highest status. And so it is with The Pā. When Vice-Chancellor Professor Neil Quigley arrived at the University of Waikato in 2015, he was surprised by the humble nature of the existing marae. As he learnt about the mana whenua, kīngitanga (Māori king movement) and raupatu (land confiscation), Quigley recognised the need for the marae to be elevated in profile, with the University’s most prominent location. And so, the site is on the summit line, a literal hillcrest in Hillcrest, Kirikiriroa. Jasmax, one of the three architects, described this as the most ambitious building in the University of Waikato’s history. Perhaps in New Zealand university history. So, where is the innovation in The Pā? Here are ‘Seven Points Towards a New Māori Architecture’:3 1. The concept is immediately legible for pōwhiri. During the welcoming ceremony, what you see is what you get. Little is hidden. A trope of modernism has been to signal political transparency through architectural transparency. The iconic frontality of the amo-maihi gable, typical to most post-colonial wharenui, is also evident to the visitor in Ko te Tangata, the University wharenui. Yet the maihi continue well beyond the tekoteko, criss-crossing and extending into the sky. From the ātea, the parti is apparent; the section is the form generator of the overall project. A sequence of portals is visible, too, upholding the rhythm of poupou-heke. Yet, the novelty of this structural arrangement speaks of a heritage transformed. 2. The central whare door departs from the asymmetry of the usual door to the left. In this case, a central door denotes the house as a whare wānanga and invokes what Tā Hirini Moko Mead refers to (in his forthcoming book on Mātauranga Māori) as the kauhanganui. It’s a liminal space which ran down the centre of pre-colonial whare and “knowledge of it influenced the design of whare and what could be done in that space”.4 With ancient Māori construction techniques (such as mīmiro),5 there was no structural reason for the pou tokomanawa (central ridge pole). And so it is with The Pā. As the glulam portals require no interstitial support, the door is free to migrate back to the middle. With traditional whare construction methods, the tāhuhu (ridge beam) still needs central support at the rear wall and outside the mahau/porch line when the door is located centrally — as is the case with Taranaki and Whanganui whare, which maintain a central front door.

3. The front mahau has been supersized. The porch in whare Māori is unique and not evidenced in other buildings of Te Moananui, such as fale, fare and hale (Samoa, Tahiti and Hawai’i). The mahau, a transitional space between indoors and out, emerged as a practical response to keeping the entry area dry and as a sheltered space to remain connected to the broader activities of the marae ātea and kāinga. In some contemporary wharenui, the mahau is evolving to be a covered exterior space capable of accommodating activities in its own right. At a recent Vā Moana symposium, Hoskins spoke of The Pā mahau as fulfilling core traditional hui and wānanga functions and being transformed through the interconnections and ‘co-location’ with other tertiary functions. At The Pā, the mahau is now 10m — perhaps the deepest in the country. Designed to facilitate whakatau (informal welcomes), hui and teaching activities, this dimension recognises the inclement Hamilton weather and the Waikato-Tainui kawa of holding pōwhiri and important hui outdoors. 4. The wharenui has an active rear elevation and a double-ended mahau. The back of the whare is now an architectural focus. The rear mahau is, however, not accessible to the interior and thus maintains the tikanga (protocol) of the whare. The rear mahau instead acts as a stage and activates a generous central atrium, incorporating food retailers, breakout spaces and a student hub that extends, via a 6m-wide bleacher stair, to the Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies. The back of the whare is, suddenly, a whole lot more interesting. 5. The whare has evolved into a multi-sided building. Hoskins cites the relevance of the cruciform whare wānanga Te Miringa Te Kakara at Waimiha (1887), built in the shape of a cross. It had four entrances and four mahau. This whare provides an historical precedent for the contemporary Pā. Distributed along one length of the wharenui is the Vice-Chancellor’s Office and senior leadership co-located with the University executive, symbolising a Treaty-based relationship. Along the other length is a north-facing loggia that connects to the existing library. 6. The interior light was made cultural. As Te Ari Prendergast has written,6 Māori architecture engages with narrative and often employs pūrākau to tell stories with underlying meaning. The Pā includes a narrative of ‘whare as light’. Whilst activated on all four sides, no side or rear windows exist. Whilst the wharenui can be deep and dark, interior light was culturated, with poupou not lit by halogens but illuminated from within, creating a sense of māramatanga or enlightenment. 7. The whakaruruhau is formed from a single gesture: heke emanate from the wharenui to unite four ‘buildings’ under one (mega-butterfly) roof. The whakaruruhau connects the wharenui to the east, the University’s executive wing to the south, a central student hub, and the refurbished Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies to the west. The proximity of the office of the Vice-Chancellor to the wharenui is startling. Between Māori and Pākehā, adjacency creates agency. So, how was such innovation made possible? The role played by the mana whenua, Waikato- Tainui, and their relationship with the University was crucial. As long as Waikato-Tainui remained present through the design, build and occupancy, then the mana of The Pā would be upheld. Waikato-Tainui owned the whenua, which was returned as part of a Treaty settlement in 1995. Mindful of the vulnerability of the institutional marae client, Tainui established the University as the anchor tenant. This joint venture demonstrates the capabilities of New Zealand architecture when there is confidence in the occupancy of whenua. The architect’s desire for innovation must be balanced by tradition. In advancing Māori Architecture, the role of ‘conservative kaumātua’ remains vital to debate, test and contend with any resistance/acceptance of new ideas. This generation typically carries the mātauranga and needs to be comfortable enacting traditions within new settings to make the experience familiar and safe for all parties. The kotahitanga of the three architectural offices, Architectus, designTRIBE and Jasmax, is: Partnership in (architectural) Practice. In reaching new heights with The Pā, collectively, they produced an international exemplar of indigenous innovation.

References

1. As at 13 February 2024, there were 2320 architects registered with NZRAB in a population of 5.1 million. 2. NZRAB Annual Report 2021– 2022, Ethnicity, p. 24. 3. As opposed to here. 4. Email from Tā Moko Mead, dated 15 February 2024. 5. Refer to my research with Dr Jeremy Treadwell and Ngāti Ira o Waioweka. eqc. Here. 6. Te Ari Prendergast, ‘Te Pūatatangi: A chorus of voices’, Te Kāhui Whaihanga NZIA Auckland Branch newsletter, 2023, pp. 4–5.

-

- Words Anthony Hōete Images Simon Devitt

- Posted 27 Mar 2024

- Sources Architecture New Zealand – March 2024 (Issue 2)

More News

Home Magazine Article – Angle Grinder

Architectural Photography, Domestic Photography, Editorial, Magazines, National, New Zealand, News, NZ Magazines

PMRE Workshops and Conference—Las Vegas, USA, November 2025

Architectural Photography, Education, Location USA, News, Talks, United States of America, Workshops

The Marfa Workshop – Texas, USA, November 2025

Architectural Photography, Education, Location USA, News, Talks, United States of America, WorkshopsIn a post-Covid Aotearoa, what happens now? Hosted by Here Magazine, this live talk gave architects 10 minutes to answer that very question

Discover the Wrightmann House, where considered architectural curatorship by Athfield Architects has given every wall a voice.