Tony Watkins and Simon Devitt on why you shouldn’t underestimate a seasoned artist

Idealog 22 November 2018

By Findlay Buchanan

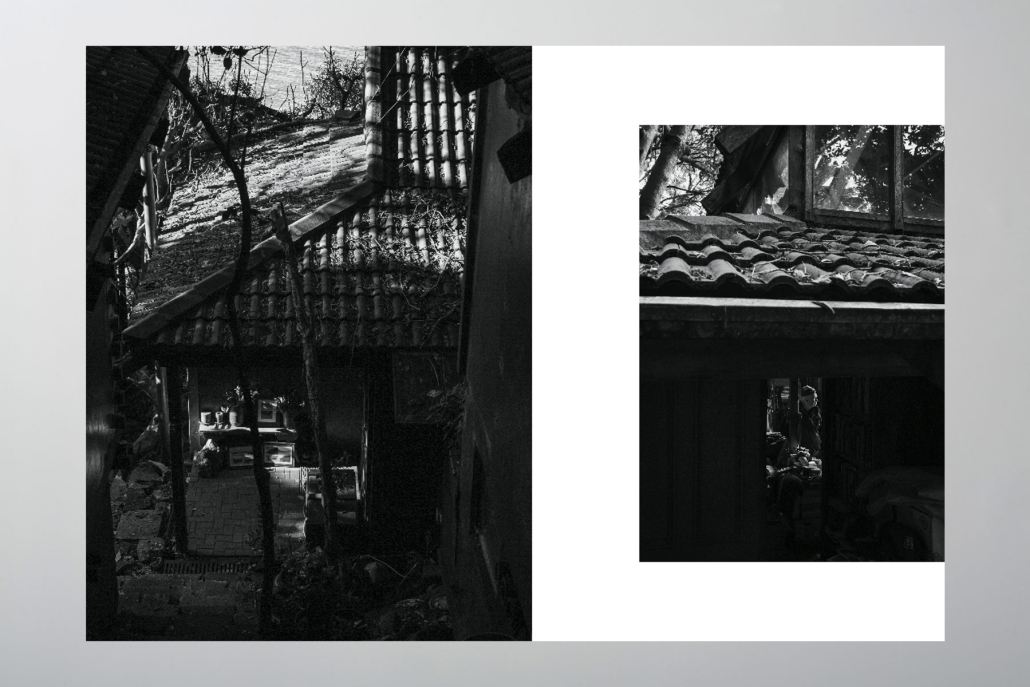

Last night, the Auckland Art Gallery launched the exhibition: Unconventional Architecture, a celebration of award-winning photographer and publisher Simon Devitt’s latest book, Ripe Fruit Vol. 2. It represents the second part of a planned series of eight which celebrates an array of New Zealand poets, architects, and writers. The book showcases maverick architect, writer and environmentalist Tony Watkins’ home in Karaka Bay, Auckland in a photographic essay. The exhibition, a one-night only membership event, saw the two venerable artists in conversation about design, unconventional thinking and the art of architecture and photography. We tracked down Watkins and Devitt to discuss the intriguing photographic series.

Amid a sold out crowd of tight-lipped and snappy looking architects stood Tony Watkins in a pair of jandals. The seasoned architect was full of voice, and rightly so, as he shared passionate views on the state of New Zealand’s architecture and the need to build around nature, instead of on top of it. The event aimed to recreate the intimate, personal setting of Simon’s images taken in and around Tony’s house, hidden from view by the trees of Karaka Bay.

While the book presents a photographic series of Watkins in his home, it also culminates a philosophy about a way of life. Part of this idea relates to age, as the series Ripe Fruits, was built on a polemic against the neglect for our older people.

“Ripe Fruit are what I deem to be people at the peak of their powers. Thus the title. And we wouldn’t say that about ourselves, we couldn’t, and we probably shouldn’t, but I can. And these people who are in their sixth decade should be celebrated.”

The first of six identities chosen in the Ripe Fruits series was Mary McIntyre, and fittingly Watkins has been the next in line, who has built and wrote about his home since 1970.

Watkins says, “It has been around about fifty years. You need time. Time is an important ingredient of architecture. You cannot create architecture quickly, you have to gather the patina of life around architecture. This is what Simons book is about, the patina that is around the place. I am insignificant, it isn’t about me – but a way of seeing the world.”

The book itself is purposefully ambiguous. Its format sees limited text composed of a poem at the beginning and Tony’s words at the end. The pictures are without captions allowing the viewer to interpret them without the framing of text.

Devitt says, “When you combine photography with a subject like Tony, and not explain to much, there is enough insight for people. I wanted people to develop their own meaning, their own ideas, and their own outcomes. They should be left wondering a little bit. The pictures should question more than answer.”

To extend from this, the book carries an idea that a building should not be seen as an object, but as a process. This is reiterated when Watkins declares: “This is a book about photography, not a book of photographs, I make a big distinction between that.”

He continues, “Photography is a way of seeing it is not a way of controlling what someone sees. Particularly in this book, because it invites you to see things differently, it invites you to look further, to look past the image, and to look forwards and backwards. It might be caught in a moment, but the moment is all of time. And that is Simon’s real skill, to have these timeless images we can go back to again and again. And every time you go back to the image you are seeing more in the image. It is not that you are seeing more in the image itself, you as a person become more able to see what the photograph is telling you and that is what I call photography.”

Devitt adds to this point, “The greatest alchemy in photography is simply starting the picture and then time adds all the context you need. The reading, and the re reading, that is the greatest alchemy of photography and architecture.”

The pair have shared a relationship of 12 years, a reflection of the photographic process which was built on trust.

“It hasn’t been a controlled process, I have let Simon wander through my life, wander through my place and I allowed him to do whatever he wanted to do and that is not what architects do. Architects are normally into power and control, they want to control an image. I said to Simon I am totally relaxed, you find whatever you want to find and he has found these photographs. I couldn’t have found the photographs as I would’ve been seeing something else.

“When I opened the first mock up of the book, I was so excited about the images. Not because they were good photographs or good images, but because they expanded my mind to see in spite of living there for fifty years more than I had seen. That is the power of photography, and the power of art.”

A memorable theme threaded into the conversations was how to support our environment with architectural practice. During the talk, Watkins points to the alarming number of native trees in New Zealand axed down for someone’s view. He says we need to introduce a love for the planet and stop referring to climate change as a ‘technical issue’.

Watkins says, “The bigger problem is climate change, it is a really big issue. Most people don’t realise that it is an architectural issue, the primary cause of climate change is anthropogenic architecture which is human centred architecture.”

“If you shifted the debate over to nature and see human beings as part of the natural world then everything changes, the whole game changes, and if we could embrace that quickly enough we would be dealing with climate change. Forget about the detail it is the first big move that matters.”

Asked how the feedback has been since the launch of the book, Watkins says, “The most wonderful feedback I had was after the RNZ Broadcast, when an email came from Mark saying he was in his garden and a kererū flew down and sat beside him on a branch and he thought of me. You cannot say more about architecture as far as I am concerned, it’s like the Japanese Haiku for me. When Mark could say that, I don’t know if I wanted anything else.”